Mise en scène encompasses the most recognizable attributes of a film – the setting and the actors; it includes costumes and make-up, props, and all the other natural and artificial details that characterize the spaces filmed. The term is borrowed from a French theatrical expression, meaning roughly “put into the scene”. In other words, mise-en-scène describes the stuff in the frame and the way it is shown and arranged. We have organized this page according to four general areas: setting, lighting, costume and staging. At the end we have also included some special effects that are closely related to mise-en-scène.

SETTING

(Lowe)

Setting creates both a sense of place and a mood and it may also reflect a character’s emotional state of mind. It can be entirely fabricated within a studio – either as an authentic re-construction of reality or as a whimsical fiction – but it may also be found and filmed on-location. In the following image, from Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006), the ornate décor evokes 17th century France and the castle of Versailles. But here the baroque detailing overwhelms the character, conveying her despair. The actress’s position in relation to the objects within the frame suggests that, as a pawn in the dynastic enterprise, Marie Antoinette is little more than a footstool.

The next shot, from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Earth Seen From the Moon [La terra vista dalla luna, 1966], provides a good example of the many and various effects that can be achieved via mise-en-scène. Although the film was shot on-location, the director’s style is not altogether realist. While he wishes to depict a shanty town in the suburbs of Rome, the colorful rubble and freshly painted buildings underscore his playful, ironic approach to the subject matter. The vibrantly clad children have no active role in the film and, since Pasolini means to criticize romanticized visions of Italian poverty, they are to be seen as location details.

x

LIGHTING

(Manrodt)

Three-Point Lighting

This arrangement of key, fill, and backlight provides even illumination of the scene and, as a result, is the most commonly used lighting scheme in typical narrative cinema. The light comes from three different directions to provide the subject with a sense of depth in the frame, but not dramatic enough to anything deeper than light shadows behind the subject.

Blake Edward’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) applied the three-point lighting technique to illuminate scenes. Though the subjects of the frame (Audrey Hepburn and George Peppard) are properly highlighted, faint shadows are visible in the background, adding to the depth of frame.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) also utilized the three-point scheme. There is enough contrast in the backlight and highlight that the people in the crowded scenes are distinguishable from one another.

High-Key Lighting

High-key lighting involves the fill lighting (used in the three-point technique at a lower level) to be increased to near the same level as the key lighting. With this even illumination, the scene appears very bright and soft, with very few shadows in the frame. This style is used most commonly in musicals and comedies, especially of the classic Hollywood age.

Sofia Coppola took a soft, high-key approach to illumination in her film Marie Antoinette (2006).

An example of the common use of high-key lighting in musicals and comedies of the classic Hollywood era is its presence in The Wizard of Oz (1939).

Low-Key Lighting

Low-key lighting is the technical opposite of the high-key arrangement, because in low-key the fill light is at a very low level, causing the frame to be cast with large shadows. This causes stark contrasts between the darker and lighter parts of the framed image, and for much of the subject of the shot to be hidden behind in the shadows. This lighting style is most effective in film noir productions and gangster films, as a very dark and mysterious atmosphere is created from this obscuring light.

One of the most noted for their use of low-key lighting in their films was Orson Welles. Used extensively throughout his film noir Touch of Evil (1958), Welles also featured low-key lighting in several scenes of Citizen Kane (1941).

COSTUME

(Mertz)

Arguably the most easily noticeable aspect of mise-en-scene is costume. Costume can include both makeup or wardrobe choices used to convey a character’s personality or status, and to signify these differences between characters. Costume is an important part of signifying the era in which the film is set and advertising that era’s fashions.

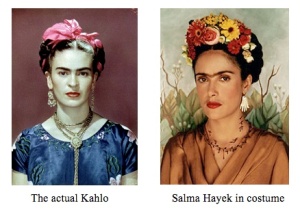

In biographical films, costume is an important aspect of making an actor resemble a historical character. For example, in Frida, the actress Salma Hayek was not only dressed in Mexican garb contemporaneous with the 1940’s, she is also given a fake unibrow to more closely resemble the painter Frida Kahlo.

In My Fair Lady, changes in costume are essential in signifying the character Eliza Doolittle‘s transformation from a ragged street urchin to polished social queen. Before, she is dressed in rags and her face is dirty, but after receiving etiquette training she is dressed elegantly in order to signify her acceptance into upper class.

In My Fair Lady, changes in costume are essential in signifying the character Eliza Doolittle‘s transformation from a ragged street urchin to polished social queen. Before, she is dressed in rags and her face is dirty, but after receiving etiquette training she is dressed elegantly in order to signify her acceptance into upper class.

SPACE (Lafauci, Macfarlane)

Deep Space

A movie uses deep space when there are important components in the frame located both close to and far from the camera. It is used to emphasize the distance between objects and/or characters, as well as any obstacles that exist between them. In Finding Nemo, there is an ongoing juxtaposition between the tank in the dentist’s office and the ocean. In this image, Nemo and Gill are discussing the possibility that Nemo’s father, Marlin, might be waiting for him in the harbor, which is visible in the distance. Deep space is used in this frame to stress how far away Nemo is from his father and the barriers separating them.

Shallow Space

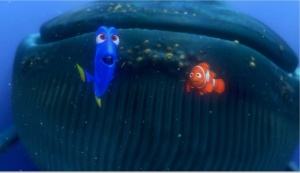

The opposite of deep space is shallow space. In shallow space, the image appears flat or two dimensional, because there is little or no depth. In this image from Finding Nemo, the whale is approaching Dory and Marlin from behind, which creates suspense for the viewer, because the fish are unaware of the whale’s presence. There is a loss of realism, but it enhances the viewing by emphasizing the close proximity of the whale to Dory and Marlin and creating concern in the viewers that they may soon be eaten.

Offscreen Space

Offscreen space is space in the diegesis that is not physically present in the frame. The viewer becomes aware of something outside of the frame through either a character’s response to a person, thing, or event offscreen, or offscreen sound. In this video clip from American Beauty, without seeing Ricky or his video camera, the viewer becomes aware that someone present in the room is videotaping Jane, who is onscreen. The noise from the video camera and Ricky’s response to Jane’s comments enlightens viewers as to what is going on. In using offscreen space, directors employ a more creative method of conveying information to the viewer.

Frontality

Frontality is when the characters are directly facing the camera, providing viewers with the feeling that they are looking right at them. In Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the director often uses frontality as well as direct address (when the character speaks to the camera). This clip is one of many in which Ferris speaks to the audience directly. This allows him to inform the viewers of his thoughts by breaking the typical boundary between the audience and the characters onscreen.

STAGING AND ACTING

(Roberts)

An actor or actress’s performance can make or break a movie regardless of how engaging the story is or how well the editing was done etc… It is the actor’s duty to bring his or her character to life within the framework of the story, and his emotional input dictates how strongly the audience feels about the film. Acting depends upon gesture and movement, expression and voice.

Russel Crowe as the lovable but fearsome Maximus in Gladiator (2000)

Performance Style

Two of the most common styles of performance in modern cinema are method and non-method acting (also known as naturalistic vs. stylized). The method actor’s job is to become one with the character’s mannerisms, dress, upbringing, etc. Essentially, he or she must be that character to the point where they are no longer distinguishable. Conversely, non-method or stylized acting relies on a more conspicuous approach to get the director’s point across. They will overact and hyperbolize certain characteristics in an effort to dramatize, or alternatively, to undercut for a comic effect.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KwkP7Gnp7ek

Daniel Day Lewis, in his Oscar Award-winning portrayal of oil tycoon Daniel Plainview in There Will be Blood (2009). Day Lewis perfectly exemplifies method acting as the audience truly believes that he has quote “abandoned his boy” in this powerful scene.

Non-method acting is much more similar to acting on the stage, and it was more common in early, silent cinema. In the absence of sound and voice, meaning was conveyed, often in an exaggerated way, through gesture and expression.

John Cleese from the comedy troupe Monty Python. A perfect example of non-method or stylized acting.

Blocking

The meaningful arrangement of the actors on the set is called blocking. The way in which the actors are positioned can show the dominance of one character over another, the importance of family or religion, and a myriad of other relationship possibilities.

As shown in this classic scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), blocking is used to show the supremacy of “The Godfather”, the submission of his “subjects”. His son is seen in the background, waiting for his chance to be in charge.

SPECIAL EFFECTS

Matte Shot

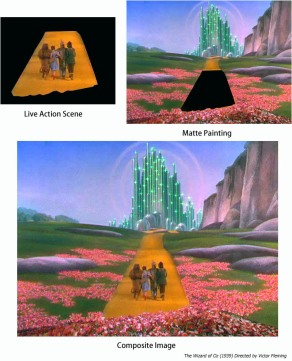

A matte shot is one in which two images are merged into one. This is a common process done to manipulate the scenery due to cost or impossibility. These images from The Wizard of Oz, demonstrate the process of creating a matte shot. The first is a frame from a live action shot of the group walking on the yellow brick road. The second is a painting of Emerald City and the surrounding scenery including the end of the yellow brick road. The third image combines these two components to create a matte shot, which gives the illusion that the actors are actually walking towards Emerald City, when in fact it does not even exist. It was clearly impossible in this case to build the scenery for this shot.

REAR PROJECTION (Manrodt)

Rear projection is a special effects technique used to give the illusion of filming a scene on location. The technique combines pre-filmed background footage with present foreground action. Rear projection was most popularized in driving sequences, when actors would sit inside a prop vehicle rigged up to a projector, which would cast the pre-filmed footage behind on a screen. This would give the illusion that the scene was occurring inside of a moving car, despite the fact that most instances of the rear projection technique looked quite amateur. While the foreground action would be keyed with the proper lighting and focus, the projected footage oftentimes appeared washed-out and weak.

The romantic comedy Down With Love (2003) uses a deliberately unrealistic-looking technique of rear projection to capture the look of the Doris Day-Rock Hudson movies of the early 1960s.