Pier Paolo Pasolini: A Man Of The Past Living In The Present

Robin Cross

NYU Gallatin, Class of 2011

Italian film director and author, Pier Paolo Pasolini, lived a life on the outskirts. Though he was a public figure, his life was anything but mainstream. Pasolini was a passionate Marxist, anti-conformist, and homosexual. He completely contradicted Italian mainstream culture. He firmly believed that post-war Italy was losing its soul as it embraced a shallow form of consumerism that ignored its rich and varied cultures. These views put him well outside popular philosophies, but ironically he chose to promote his iconoclastic ideas through the most modern method of all: popular cinema. Pasolini was a modern man in search of the never found past whose work lives on into the future; he is a man of all eras.

After World War II, Italy transformed from a poor fascist country into a prosperous industrialized nation. With the sudden loss of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, Italy quickly transitioned to a world of innovation and creativity. Design products were being mass-produced and exported around the world. This new era of industrialization created an economic boom, now referred to as the “economic miracle,” and with this miracle came a newfound consumer consciousness. Italians suddenly had disposable income to spend on the finer things. A shift of culture occurred in which everything fell under the reign of consumerism. Many people were happy with the sudden burst of wealth and access to social mobility, but Pasolini felt otherwise. He saw the negatives in the modern, consumerist culture, particularly the loss of sub-proletarian cultures. Pasolini’s nostalgia for the repressed archaic cultures is engrained in his films, as he often searched to represent the bigger spectacle of reality.

Political theorist and philosopher Antonio Gramsci was one of Pasolini’s biggest influences. Gramsci’s philosophies of cultural hegemony were directly reflected in Pasolini’s opinions of Italy’s modern culture. According to Gramsci, cultural hegemony is a concept in which a culturally diverse society is dominated by the ideologies of the ruling social class. These ideologies are seen as universal, though they actually only benefit the ruling class. Pasolini saw the dominant consumerist culture of post World War II Italy as the ruling ideology that repressed sub-proletariat cultures. Consumerism was the accepted norm. Gramsci suggests that established norms and institutions be investigated rather than immediately be considered natural. Pasolini concurs, as he does not believe in institutionalized schools nor considers himself a Catholic for they coach conformed ideologies. He states:

School, that is to say, to that organization and culture organism which has totally diseducated you and places you here before me as a poor idiot who has been humiliated, indeed degraded, incapable of understanding, caught in a trap of mental pettiness which, apart from anything else, causes you suffering. (27)

The best way to learn is through the lessons of life and reality. Parents and institutions impose ideologies upon innocent minds. As a result, the beliefs of the dominant culture are directly taught and instilled in new generations, pushing the presence of subcultures further and further away.

Pasolini believes in the revolutionary role of the Italian peasantry. As a Marxist, he found the need for a national movement to take place, but with the Gramscian ideology behind it. Pasolini thought all Marxist intellectuals came from a privileged bourgeoisie background and held Marxist beliefs based on morality and humanitarianism whereas Gramscians have passion and concern (Stack 24). Pasolini’s Gramscian version of Marxism isolated him from the hegemonic elites that his film career had led him too. Instead of becoming a part of the aristocratic circles, Pasolini placed himself in the fields with the peasants. As Oswald Stack describes, “He lays increasing stress on the need to restore an epic and mythological dimension to life, a sense of awe and reverence to the world: a sense which, he believes, the peasantry still sustain, though the bourgeoisie has done all in its power to destroy it” (9). Pasolini did not support the proletariat for moralistic purposes. Rather, he had a genuine passion for their culture and sense of being; he wanted to instill a lost lifestyle, one that is not of the bourgeoisie. Pasolini states:

My hatred for the bourgeoisie is not documentable or arguable. It’s just there and that’s it. But it’s not a moralistic condemnation; it is total and unmitigated, but it is based on passion, not on moralism. Moralism is a typical disease of part of the Italian left, which has imported typical bourgeois moralistic attitudes into Marxist, or at any rate communist, ideology. (qtd. in Stack 26)

Pasolini wanted to take part from the outside. His love for non-hegemonic cultures was authentic; he integrated himself into it.

In accordance with Greek tragedies, Pasolini believed that sons are predestined to pay for the sins of their fathers (11). At first thought, he did not apply Greek ideology to his life, but then he reached the realization that he belonged to the generation of fathers. He believed that the youth of the post-war era were living his and his peers’ sins. But for what sins exactly were the sons paying for? Pasolini did not consider fascism to be the sin; it was what came after fascism that caused Pasolini great shame. Pasolini explains:

The sin of the fathers is not only the violence of power, Fascism. It is also this: the dismissal from our consciousness by we anti-Fascists of the old Fascism, the fact that we comfortably freed ourselves from our deep intimacy with it, the fact that we considered the Fascists ‘our idiot brothers’; secondly and above all, the acceptance (all the more guilty because unconscious) of the degrading violence, of the real, immense genocides of the new Fascism. (16)

The new fascism that Pasolini was referring to was the controlling consumerist culture, the culture of the bourgeois. He considered this new fascism, the dictator of consumption ideology, the ruin of all ruins. He continued to say that the biggest guilt for fathers is the acceptance of bourgeois history as the only history, as that lacks the characteristics and stories of everyone that does not fall into this hegemonic class. Pasolini viewed poverty as the greatest ill in the world and was greatly saddened by the fact that those of the poorer classes are condemned to replace their unique culture with that of the ruling class. His passion for the sub-proletariat lies in their replaced and forgotten culture.

Conformism is one of the main causes of cultural hegemony. The unification of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie occurred under the dictator of consumer goods. The newfound consciousness took over the divide and in turn created a new one. The conformism to a consumerist lifestyle corrupts innocent cultures. Pasolini explains, “National conformism, the conformism of the ‘system’ has become infinitely more conformist from the moment when power became consumerist power, therefore infinitely more efficacious in imposing its will than any other preceding power in the world” (20). The influence to follow a hedonistic lifestyle as consumers renders a greater persuasion than any other institution. Unfortunately, as a result, the road to modernity erased memories and cultures of the past.

In this clip from Pasolini’s short film, La Ricotta, Orson Welles is a movie director that is being interviewed by a journalist about the current film he is making. Welles allows four short questions, in which he responds that the Italian bourgeoisie is the most ignorant in all of Europe. When the interview is over, Welles decides to read this poem to the journalist. The poem was actually one that Pasolini had written for his book of poetry. Welles’ character was meant to resemble Pasolini as a director in this short neo-realist film. Pasolini’s poem speaks of a man who is of the past yet living a life of modernity without tradition. This poem reflects Pasolini’s realization that he is of the generation of fathers of sin. It states, “And I, a fetus now grown, roam about more modern than any modern man, in search of brothers who are no longer.” He is in search of the archaic and cannot find it, as tradition was lost to modernity. This clip directly reflects Pasolini’s feelings about cultural hegemony in that the old is replaced by the new due to mass conformity.

Pasolini chose cinema as his method to apply his voice of meaning to society. Rather than create generic “blockbuster” films, Pasolini implanted intellectual messages and morals within his films that the viewers must follow and detect. Through cinema, Pasolini was able to communicate with everyone, as he believed cinema was a language of its own. Pasolini had always wanted to change nationalities and learn another language, but then he realized that the language of cinema belongs to all nationalities and all classes, not just one nation with one language and one culture (Stack 29). Cinema is a language of transnational signs. Pasolini explains:

The cinema is a language which expresses reality with reality. So the question is: what is the difference between the cinema and reality? Practically none. I realized that the cinema is a system of signs whose semiology corresponds to a possible semiology of the system of signs of reality itself. (qtd. in Stack 29)

Pasolini felt that within the cinematic world, he was always at the same level of reality. He discovered his true passions: a love for life and existential reality. Within cinema, Pasolini was able to express reality through symbols of reality itself. A tree is expressed through a tree, a person with a person. His view of lost tradition is expressed through his own poem. Pasolini used cinema to express the loss of cultures to the modern unification of culture under the roof of consumption.

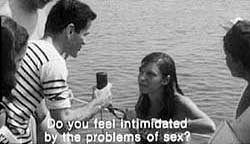

What was the reality of post-war Italy? Pasolini tried to capture the essence in his documentary Comizi d’Amore. In this 1965 documentary, Pasolini ventures around Italy to interview people in their natural settings. As stated in the above clip, Pasolini is trying to find the real Italy. What constitutes Italy: the seen or unseen? Knowing Pasolini’s history, it is obvious that he was interested in the unseen, but it is the combination of both that creates the current history. His method of acquisition of information is to ask Italians about sex and love, a topic of conversation that is constantly switching directions in the midst of the economic boom and the transition to modernity. Pasolini presents questions of sex, morality, divorce, homosexuality, and prostitution to a variety of people ranging from elites to peasants. The discovered inner-dialogue of the documentary is similar to that of La Ricotta: conformism. Pasolini states, “You could say it is the decadence of integration into society. The average man is proud of being what he is and wants everybody else to be the same” (qtd. in Stack 62). Therefore, everyone is integrated into society by conforming his or her ideology to that of the mainstream beliefs. Very strong underlying messages can be found within this documentary, but not many Italians found them. Comizi d’Amore was not a widely accepted film; it hardly was played in Italy and did not travel internationally. Pasolini did not expect the film to go international because of what would be lost in translation. With the comparison of the Italian dialects and the jokes hidden within, many details would be lost in translation. Pasolini explains, “He would only be able to get the sense of the answers, not the feeling” (qtd. in Stack 65). So why was the film not praised within the Italian borders? Pasolini states, “It’s simply that the public saw themselves reflected too faithfully. The ideological and social world that Italians live in only becomes meaningful to someone who is outside it; all people living in it saw was their own everyday life reproduced” (qtd. in Stack 65). Italians could capture the feeling but not the answers. The Italians were unaware of the significant point that Pasolini was making: everyone was living under the same hegemonic roof. They did not see the irony. Perhaps, it was only those that lived outside of the accepted hegemonic lifestyle that were able to see the meaning.

With the use of neo-realist technique, Pasolini was able to shape his documentary into a metaphorical statement of reality. Neo-realism is a cinematic development that formed in Italy after World War II when artists searched for an aesthetic approach to represent their interpretation of the brutal reality they were living. Neo-realism portrays reality philosophically speaking. A major component of neo-realism is the importance of setting: the set is a character in and of itself along with conditioning the characters within it. In Comizi d’Amore, Pasolini captured the Italians in their natural, representative settings. He used non-hegemonic landscapes, such as peasants working in the isolated fields of Sicily. These settings held importance of their own.

Pasolini often interviewed people on the beaches while in search of the “real Italy.” Through a cinematic lens, the beach symbolizes an edge, a limit point, and the end. On the beach, Pasolini encounters a man with his young boy who describes the state as an extension of the family, a belief that only fits perfectly with those that fit into the hegemonic culture. The state does not represent prostitutes or homosexuals. Angelo Restivo describes, “What Pasolini uncovers, then, is the ghost that haunts any attempted mediation between the national and the local, and which the advertising of the period subtly reinvokes: the ghost of fascism” (85). Pasolini constantly found the old fascism confronted with the new. By controlling the cuts and sequence of segments in his editing, Pasolini was able to manipulate the underlying meanings to his advantage by contrasting intellectuals of the north with peasants of the south. He then used voiceovers to connect the dots. One of the most essential factors that connected this documentary to the real was the technique of placing himself into the film. Pasolini often showed clips of himself as the actual interviewer in the documentary, something that was very unusual in the documentary realm. Being able to see the interviewer brings a very real feeling to the film. With the neo-realist approach to questioning the self and reality, Pasolini was able to show the taboos of sexuality, in the context of a very confused debate in which no one set of people had a direct answer.

This clip demonstrates Pasolini’s exact problem with cultural conformism: what is viewed as not normal should be repressed to the point of extinction. Therefore, all cultures that lie outside of normality, such as homosexuality and prostitution, should be condemned and hidden. As this man states, the point of repression is to provide a hegemonic path of normality for the next generations to follow. In reality, this dialogue creates the construction of the other. How in discourse do we define the other? If someone lies outside of normality, but is tolerated, is that not that the same as being condemned because one still has the label of being different? To tolerate someone’s difference is the same as condemning the difference because it is still recognized as abnormal. Tolerance is not acceptance. Cultural hegemony represses all abnormalities; it creates a destructive sense of the other. Pasolini elaborates:

His ‘difference’—or better, his ‘crime of being different’—remains the same both with regard to those who have decided to tolerate him and those who have decided to condemn him. No majority will ever be able to banish from its consciousness the feeling of the ‘difference’ of minorities. (22)

Every person regarded to as “the other” is forever more conscious of being different, trapped in what Pasolini calls the mental ghetto. He laments, “So long as the odd one out lives his difference in silence, shut up in the mental ghetto assigned to him, all is well; and everyone feels gratified at the tolerance they are granting him” (23). As long as the homosexual withholds his sexual desires, he is tolerated in society. As long as someone pretends to fit into the hegemonic culture, all is well. The answer is to conform. The result is the loss of subcultures. Pasolini believed the only solution to be that of cold rejection and denunciation of the mainstream culture. According to Pasolini, anyone that accepts the tolerated transformation and therefore deterioration of culture does not fully love the other human being. They are ripping the blood from their peers and forcing them to live an undesired life, a life trapped within the limits of normality and in a mental ghetto. For these reasons, Pasolini found the need for a Gramscian revolution and political activism.

In Pasolini’s opinion, every person has the social responsibility to be politically conscious. Every person has the tools to be an informed human being, and it is our responsibility to stay informed, as we are responsible for reality. Humans cannot just stand by obliviously without taking into account their surroundings. In honor of this belief, Pasolini made the short film, La sequenza del fiore di carta, in 1969 to be a segment of the film Amore e Rabbia. The short montage was made of only three traveling shots combined with imposed images from the early half of the 1900s. The protagonist, Riccetto joyously dances along a popular Roman street with a giant red flower in his hand. His oblivious nature distracts him from reality and the brutal history of his country. God attempts to bring Riccetto’s attention to his surroundings but fails, and, alas, Riccetto is condemned to death. Pasolini believed that the course of life can change at any moment up until death, so it is impossible to define it until it is over. Riccetto never changed. The innocent can never use innocence as an excuse; everyone must be aware. There are moments in time that cannot be neglected, and Riccetto neglected important history. The long take that Pasolini uses in La sequenza del fiore di carta is a metaphor of life and existence. It is a record of the present moment, a moment in which there is allowance for social justice and political action. Modernity allows for this discourse. Man is constantly confronted with layers of history that are embedded in the present. Pasolini never wanted to reconstruct the past, but rather highlight the connection of the past to the present. He states, “I should say that I continuously felt the need to refer to contemporary life, so that things would never be historically reconstructed, but always in reference to our experience of history. Not the past disguised as the present but the present disguised as the past” (qtd. in Steimatsky132). In this clip from the short film, Pasolini is super imposing the past onto the present.

The heavy images of the past represent the drastic moments of history that cannot be escaped. Pasolini states, “That there are moments in history when one cannot be innocent, one must be aware; not to be aware is to be guilty” (qtd. in Stack 131). Not to be aware of subcultures and their near extinction is a guilty act. Pasolini believed these cultures are a part of history and should not be lost to the representation of the bourgeoisie. Pasolini is nostalgic for the archaic in all senses.

Pasolini turns cinema inside out to the raw semiology of reality. As all neo-realist films do, he heightens the consciousness of the self and reality. Pasolini implants messages and morals of society and human responsibility. He represents the current while infiltrating the past. What is most evident in the work of Pasolini is his modern consciousness that is nostalgic for the archaic. His films are constantly confronting the combination of the archaic and the modern. The history, the culture, the dominant, and the repressed are all represented and confronted. In La Ricotta, a modern man misses the archaic. In Comizi d’Amore, a homosexual is confronting the taboos of sexuality and love. In La Sequenza del fiore di Carta, a Marxist shows the importance of a political conscious. Pasolini’s films are reflections of his thoughts and opinions of society. Cinema is his language. The viewers are his students. Life is his lesson. Pasolini’s goal was to detract man from the conformation imposed by institutions. Current reality is the purest form of the past and present. Culture is the eyes of the viewer. Decisions are to be made individually, not collectively. Pasolini passionately preaches, “A man of culture, dear Gennariello, can only be either far ahead of his times or far behind them (or even both at once; as in my case). That is why he is listened to – because in his existence here and now, in his immediate actions, that is to say, in his present, reality possesses only the language of things and can only be lived” (32). In writing of Pasolini it is easy to get the tenses mixed up. He lived in the age of modernity, but he was obsessed with how that modernity was erasing the sub-cultures of the past. He was embraced by the glitterati, but he embraced the proletariat. He spoke for the past, but used language of modern cinema. He died many years ago, but his works are alive with passion. He was ahead and behind his times, but he is also of our time.

Works Cited

Adams, Sitney. Vital Crises in Italian Cinema. University of Texas Press, 1995. 172-196. Print.

“Cultural Hegemony.” Wikipedia Foundation, Inc., 2011. Web.

Pasolini, Pier. Lutheran Letters. United Kingdom: Carcanet New Press Ltd, 1983. Print.

Restivo, Angelo. The Cinema of Economic Miracles. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2002. 77-87. Print.

Stack, Oswald. Pasolini on Pasolini. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1969. Print.

Steimatsky, Noa. Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Past in Postwar Cinema. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008. 117-137. Print.